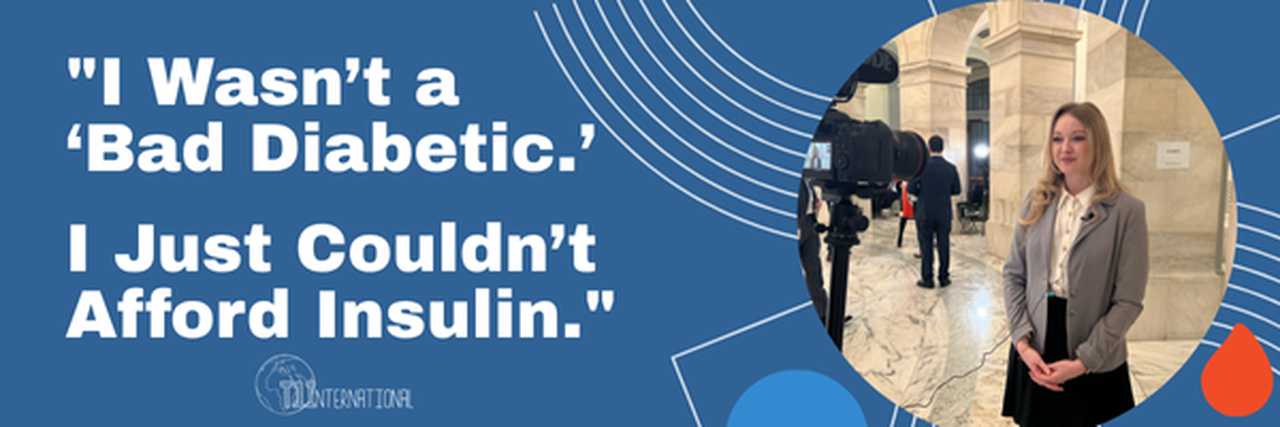

"I Wasn’t a ‘Bad Diabetic.’ I Just Couldn’t Afford Insulin."

11 Jun 2025, 5:06 p.m. in #insulin4all USA by Lacy McGee

One of the strangest realizations I’ve had—and something I’ve heard echoed by many others with diabetes—is that we often don’t realize we’ve been rationing insulin until we look back. I wish I had known when I was younger that there was a term to explain the years I struggled to afford insulin. Not because I didn’t care about my health, but because there were no generic alternatives and I was underinsured. Back then, I didn’t have the words to explain it. I just knew I was doing whatever I could to survive.

I’ll never forget the endocrinologist who told me I was “noncompliant” after seeing my A1C of 7.5%. I had waited six months for that appointment—she was the only one in the area who accepted my soon-to-expire insurance. I’d driven 600 miles to get there. Instead of helping, she wrote a prescription for only a one-month supply and essentially told me that I wasn’t trying hard enough.

Later in graduate school, a professor cornered me in the locker room after a severe low blood sugar episode and said, “No offense, but you’re a terrible diabetic. You’re 22—you should have this figured out.”

I was trying harder than they knew. But I didn’t have the means.

Diabetes is an incredibly unique experience that requires constant decisions—many of which are dictated by what our insurance covers, or worse, what we can pay out-of-pocket. Too often, people around us equate “control” with discipline alone, ignoring access. Through the years, I’ve been asked, “Is your diabetes under control yet?” As if it’s that simple.

That’s why, when I heard about T1International’s campaign for patent reform, I knew I had to get involved.

Why Patent Reform Matters

I was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes at 17, the same month I left home for college. I aged out of Medicaid at 21, just as I started my Doctor of Physical Therapy program. My school’s health plan didn’t cover my insulin adequately. I lived off expired insulin stockpiles, stretched what little I had, and accepted or bought insulin from strangers just to get by.

I couldn’t afford a doctor. And even if I could, I couldn’t afford the prescriptions. I chose my food carefully to avoid using too much insulin. I bought the cheapest test strips I could find and went many hours without checking my blood sugar. That’s not poor diabetes management—that’s poverty management.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Our patent system could encourage competition and innovation to drive prices down. Instead, system abuse enables monopolies to drive prices up. And patients like me pay the price.

The Hidden Cost of “Innovation”

Current U.S. patent laws allow pharmaceutical companies to extend the life of their patents through tactics like evergreening and patent thickening—adding small, often non-innovative changes to extend monopolies and block generics from entering the market.

Insulin has existed for over 100 years, yet due to how it’s regulated, it never had a true generic pathway until recently. Even now, options labeled as “authorized generics” (like Insulin Lispro) haven’t received true generic pricing. That means insurance plans often treat them as brand-name drugs, charging outrageous co-pays—sometimes 50% of the list price. Access to the right insulin matters. It shouldn’t be a privilege reserved for the few who can afford it.

What Needs to Change

Thanks to regulatory updates in 2010, there’s now a pathway for biologic medications like insulin to have biosimilar and authorized generic versions. But it’s not enough. True generics remain largely out of reach, and attempted reforms haven’t meaningfully lowered prices.

That’s why we need robust patent reform now.

T1International’s current mobilization effort calls on Congress to stop the abuse of the patent system. We’re urging lawmakers to take a closer look at evergreening, ensure faster generic and biosimilar competition, and put patients—not profits—first.

Why I’m Speaking Out

My story is far from unique. It’s just one of thousands. And that’s exactly why I’m telling it.

I lived through the chaos managing a life-threatening condition with expired insulin and no support. I was judged by individuals who didn’t understand the barriers I faced. I’ve watched others go through even worse.

I’m choosing to speak up—not just for myself, but for every diabetic who’s ever been forced to choose between rent and medication. Between groceries and glucose monitoring supplies. Between life and death.

Together, we can push for patent reform—and make sure no one else has to live like this again.