The Politics of Diabetes in Nigeria

24 Nov 2016, 9:56 a.m. in Global Stories by Olafimihan Nasiru Titilope

Recently, USA Senator Bernie Sanders released a series of tweets attacking insulin makers. He followed that with a letter sent by himself and his counterpart in the House of Representatives to the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, urging an investigation of insulin makers for price collusion. Perhaps this interest in diabetes is due to the fact that the condition runs in his family. Senator Jeanne Shaheen was noted several years ago to be committed to ensuring that diabetes is a "priority for legislation no matter what happens in the election". Her interest in diabetes could also be linked to her identification with her diabetic granddaughter. Moreover, the recent revelation by the UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, on her Type 1 diabetes status, in addition to the functional relationship between the UK Parliament and several diabetes groups in the UK, points to the fact that supporting people with diabetes is an interest for UK politicians.

Support of people with diabetes and other non-communicable diseases from politicians is a common trend across the developed countries, and this has propelled them to advocate, create legislation and make policies for the education, prevention, diagnosing and management of diabetes in their respective countries.

One of the tweets by Bernie Sanders on his twitter handle reads "in the richest nation in the world diabetes patients are being forced to decide between eating and paying for the drugs they need". I was prompted to respond by comparing the condition of the people with diabetes in poor and unstable nations, such as Nigeria, with those in rich countries. Also, I reacted to the letter by Bernie and his colleague on insulin price by asking who will be the defenders for the "weak and helpless" people living with type 1 diabetes in poor countries like my country of Nigeria.

My last response was inspired by the attitude of politicians across Africa, especially Nigeria where disclosure of true health status of politicians seems abominable whether they are being affected by common diseases or deadly ones. Their practice is to embark on medical tourism in developed countries for treatment and management of their diseases secretly, while people speculate about their health status. For instance, former President Olusegun Obasanjo was forced to disclose his battle with diabetes over a number of years by his desire to get votes for his successor who later died in government, due to an undisclosed ailment. This was at the tail end of his (Obasanjo) eight-year reign.

Nigerian politicians fail to identify with non-communicable diseases, especially diabetes, despite the fact that many of them are believed to be affected by it. Their ability to travel abroad for treatment does not give them any inspiration or encouragement to make specific serious legislation, policy or advocacy that is needed to support the common people on the care and management of diabetes.

Many are being killed by the disease due to their helplessness. Some of the problems are as follows:

- absence of any specific health policy or program on diabetes

- lack of appropriate medical facilities for diagnosis and care

- inadequate funding for non-communicable diseases

- shortage of diabetes specialists and caregivers

- inadequate education on prevention and management of diabetes

- absence of any parliamentary resolution on diabetes

- absence of any regulation on access to and price of diabetic drugs (especially insulin)

According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), in 2015 out of 415 million people living with diabetes in the world, 75% are in poor and middle income countries, with Sub-Sahara Africa accounting for 14.2 million. The prevalence rate of diabetes in Nigeria is 1.9 percent for adults, and among the five million people that die from diabetes annually across the world, Nigeria accounts for more than 40,000. Relatively, Nigeria leads in the number of incidence of and mortality rate from diabetes in Africa.

Meanwhile, the current economic condition, a result of economic recession, in Nigeria is making self-management of diabetes unaffordable for the people living with diabetes. The price of diabetes supplies has skyrocketed to about 150% increase within eight months.

Choosing myself as a typical example of an average person living with diabetes in the country, my monthly costs of supplies currently within Lagos metropolis could be broken down as follows:

| Insulin (Mixtard of 100 IU) | $12 per vial |

| Glucometer (Accu-chek) | $19 per meter |

| Syringes | $6 per pack of 100 units |

| Test strips | $11 per pack |

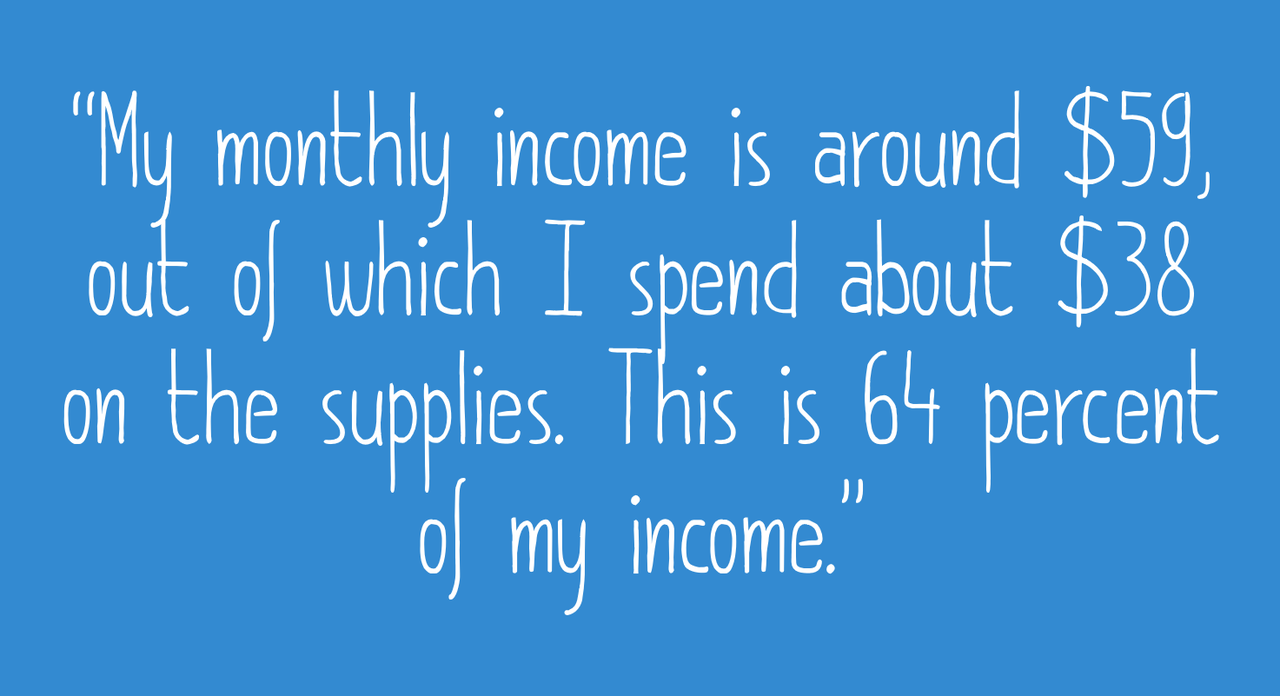

These prices are in Lagos, which is the major commercial city in the country. In other cities and towns most of the supplies are either much more expensive or not available. Meanwhile, my monthly income stands at around $59, out of which I spend around $38 on the supplies (64%). The cost of my transportation and other implicit costs are yet to be included in my spending.

Despite all the available statistics on diabetes (though the figures are actually underestimated because of absence of credible medical data from the country) and the plight of the people living with diabetes in managing the condition, there is no serious political will on the part of our policy makers.

Nigeria is used as an example here to represent all the poor and politically unstable countries of the world. The conditions of the people living with diabetes in these countries, especially in Africa, need urgent and serious actions on the part of their politicians. They need to support adequate management as well as prevention to reduce the rate of prevalence. So, I ask the question again: ‘‘who will fight for the 'weak and helpless' people living with diabetes in poor countries?’’ I hope our politicians will start to realize that the burden of diabetes will not go away, and that they will step up to the challenge.

Olafimihan Nasiru is 39 years old. He holds a B.Sc. and M.Sc. in Economics. He was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 2004 and currently resides in Lagos, Nigeria.