Reminder: Eli Lilly Has Been Exploiting T1Ds Since 1922

11 Apr 2019, 5:47 p.m. in #insulin4all USA by Audrey Farley

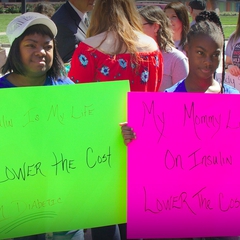

Yesterday, the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee held a hearing in which insulin-makers testified about their role in skyrocketing insulin prices. For #insulin4all advocates watching, it was encouraging to hear representatives like Joe Kennedy and Nanette D. Barragán demand answers about price increases, profits from insulin, and the nebulous “innovation” that purportedly drives costs.

It was less encouraging to hear lawmakers, including chairwoman Diane DeGette, conclude that “the system is working in ways that no one anticipated.” Such a statement suggests that insulin prices are an accident or the product of a convoluted system not intended to harm. While it is true that PBMs and insurers have altered the landscape in unforeseeable ways, it bears clarifying that the drug industry has sought to exploit diabetics for commercial gain since the discovery of insulin nearly 100 years ago. A history of Eli Lilly’s role reveals that insulin prices are not an accident—and that the system is working exactly as anticipated.

Unbeknownst to many, Lilly wasted no time in trying to establish a monopoly on Banting’s discovery. When news broke of the Canadian’s achievement, Lilly sent research director George Clowes to Toronto to attend a lecture and determine if the discovery was legitimate. If it was, and if Lilly acquired the rights to develop it, insulin could spike his firm’s profits and reputation. After the lecture, Clowes sent a three-word telegraph to his boss, J.K. Lilly (son of Eli): “This is it.”

According to the authors of Breakthrough: Elizabeth Hughes, the Discovery of Insulin, and the Making of a Medical Miracle, Clowes went home and conferred with J.K. Lilly, who instructed him “do whatever he had to do to secure a role for the company in the development of insulin.” Clowes began to hound Banting and his team with letters and visits threatening of an “insulin aristocracy” and demanding to know how many more diabetics had to die before they authorized Lilly to mass-produce the drug. Clowes also warned that, without a patent for insulin, any quack off the street could attempt to prepare the serum, and this would endanger diabetics.

Banting, his co-discoverers, and others on the Insulin Committee secured a patent for both the product and the process, and issued a one-year license to Lilly. This year, designated an “experimental period,” would give both Lilly and researchers in Toronto’s Connaught Laboratories a chance to perfect the process. But a private letter from J.K. Lilly to Clowes outlined the drug company’s real strategy: “create [insulin] centers in every possible place, thus security priority and cementing the doctors to us.” The plan, in other words, was to head off competition.

How did Lilly “cement” doctors to itself? With samples, of course. Historian John Patrick Swann explains that Lilly circulated insulin for free for much of the experimental period. This didn’t help the company recuperate its significant start-up costs, but it was a step toward achieving the greater goal: “supremacy in the insulin market.” Many physicians, including Elliott Joslin, fell for it.

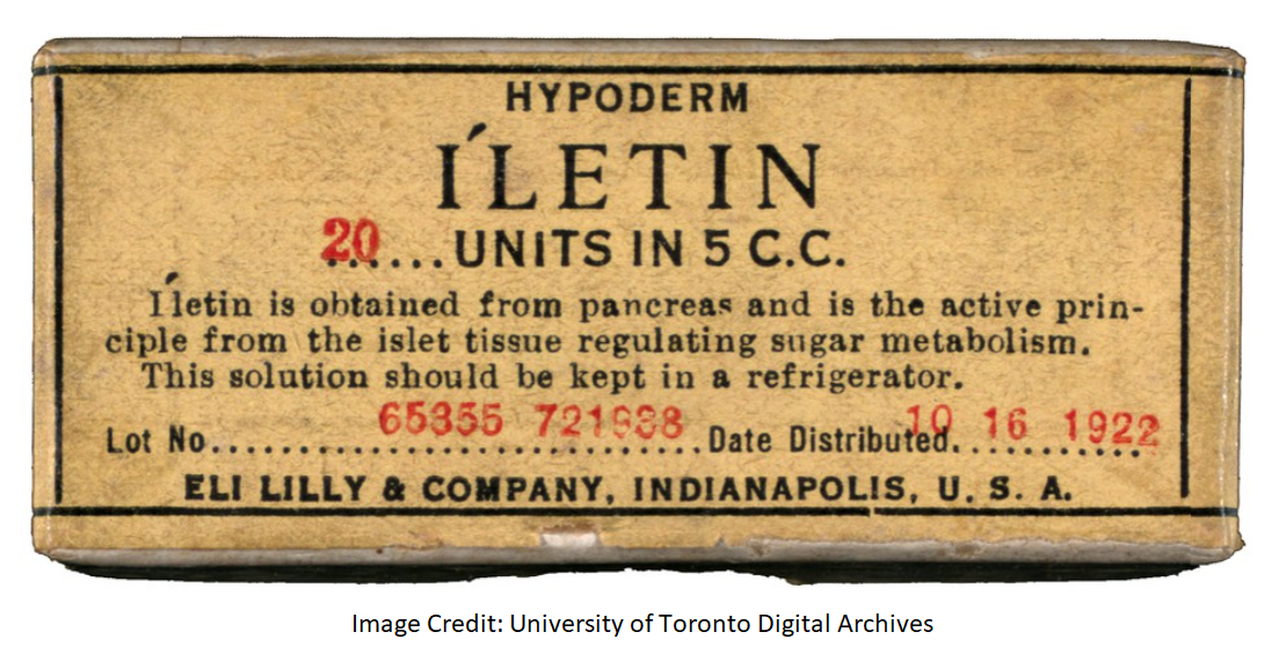

Another tactic? Swiftly slapping a trade name (“Iletin”) on the drug. Though irked, the Toronto team agreed to allow use with two stipulations: 1) the words “Insulin, Lilly” were to follow on advertising materials and 2) research must refer to the hormone, “insulin.” Lilly ignored this directive because, well, how could the company establish a monopoly without a trade name? The Canadians had to remind the folks in Indianapolis of this agreement.

Well before the experimental period ended, Lilly did not feel secure in its ability to “saturate” the market with its product after the May deadline. So, Clowes requested an extension. He claimed, among other points, that Lilly deserved to recuperate development costs, which left Banting and his colleagues scratching their heads. If recuperating costs was so urgent, why wasn’t Lilly charging patients for the drug? Facing scrutiny for favoring the company, the Insulin Committee dismissed the request.

This didn’t stop Lilly from making a pitch for its true aspiration: full control of the market. In early 1923, J.K. Lilly instructed Clowes to petition Toronto for an exclusive license to manufacture insulin, claiming this was best for diabetics. Without competition, Lilly insisted, the company could “produce at the lowest cost, test at lowest cost, sell at lowest price, and be able to give, without charge, much larger quantities for indigent cases.” The Canadians didn’t bite.

Lilly was still determined to prevail. In March, the company went behind the backs of the Toronto team to file an extensive patent application for the isolectric precipitation method (a purification process). According to Swann, researchers thought the application so broad that, if granted, “it would essentially defeat the Toronto patent application and give Lilly an American monopoly on insulin.” Determined to avoid this, the Canadians requested several changes to the application. Clowes sent a telegraph promising to revise it accordingly. This never happened.

Before the experimental period ended, the manufacturer even insinuated itself into discussions of the standard “unit” to be adopted by clinicians, as this was bound to have an economic impact. According to historian Christiane Sinding, this level of involvement on the part of a commercial actor was unprecedented.

Ultimately, Toronto authorized a short extension to the experimental period and then began to issue licenses to other firms. Because it took time for others to establish the means of production, Lilly remained the only producer in the United States for another year. With this head start, the company easily maintained dominance. In 1923, the drug was the highest-selling product in the company’s history, and profits from it accounted for over half of the company’s revenue. There was no immediate need to raise prices because Lilly was already raking in money from diabetics.

Over time, and as others began to produce insulin, the company adjusted prices without much notice. This changed in 1941, when the manufacturer, along with Sharpes and Dhome and E. R. Squibb and Sons, was charged with violating anti-trust laws. A federal grand jury indicted all three. The corporations were fined $5,000, and the officers, $1,500. (Squibb was later acquired by Novo Nordisk, and Sharpes and Dhome stopped producing insulin and merged with Merck.)

This case is often cited as the birth of the “business of diabetes,” as it was the first in a series of anti-competitive lawsuits targeting insulin manufacturers. But the “business of diabetes” did not spontaneously emerge mid-century. Corporate stakeholders found underhanded ways to profit from diabetic lives before most affected individuals had even obtained their first injection. And now that Congress is investigating insulin manufacturers, it is important to acknowledge the full scope of their involvement.

Otherwise, it is easier to believe claims that the industry inherited, rather than created, a “broken system.” For nearly a century, Eli Lilly has sought to abuse patents and create monopolies within the market. Given that the original patents and licenses for insulin were acquired under such questionable circumstances, and with the explicit goal of establishing exclusivity, policymakers should consider reforms such as price caps and breaking patents, and not just eliminating “middle men” (PBMs). Bold measures like these would inhibit the drug industry’s century-long abuse of diabetics, and they would honor the legacy of Banting, his co-discovers, and the many others fighting for #insulin4all.